This article was originally published on The Atlantic in the wake of Sandy Hook.

I was 16-years-old, a junior at Heath High School in Paducah, Kentucky. Born and raised in the small Western Kentucky town, I was the fourth generation of my family to attend Heath. My great-grandparents had skipped out on a basketball game to ride the ferry across the river and get married in Illinois. My great-aunt had been the home economics teacher for years. My mother had been the prom queen.

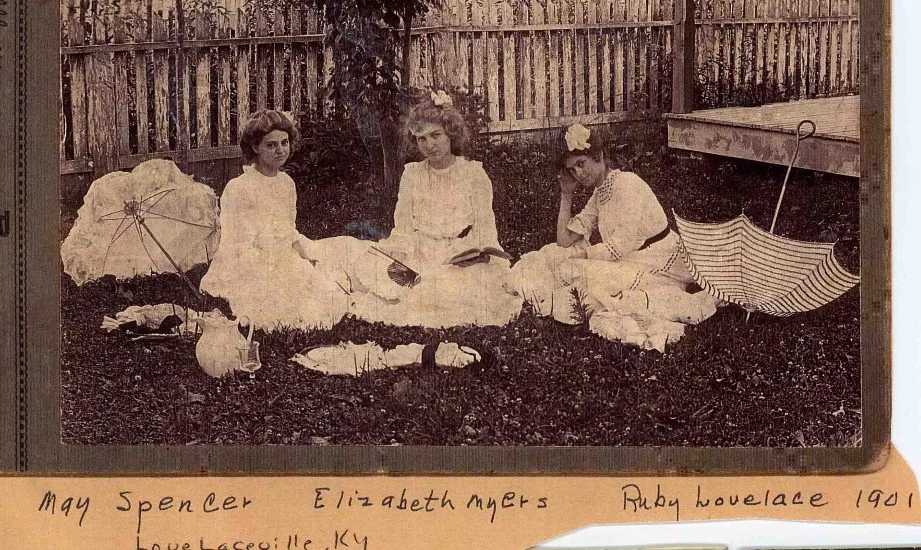

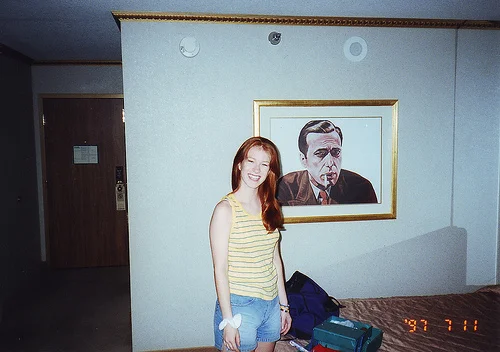

It was a cold, gray December day, the first after Thanksgiving break in 1997. Not owning a license yet, I rode to school with my friend Beth and her dad. I remember I was wearing my brand new blue fleece from the Gap that my stepdad had given me as a reward for getting all A's that semester.

We were running late, but as we circled the parking lot, I noticed a large group of students standing outside the gym -- mostly upperclassmen, including a boy I had a crush on. One of our classmates ran up to Beth's car and pounded on the window.

"Some guy just started shooting people!" he yelled.

Beth's dad told her to drive across the street to the elementary school and park. I told both of them I was getting out to see what was going on. I suspected some boy had gotten mad at his girlfriend and used a hunting rifle to seek his revenge. Just a few months before, a student in Pearl, Mississippi, had gone to school and shot his former girlfriend. As I walked past the group of upperclassmen, I noticed my crush looked pale and shaken. I asked him what was going on.

"I don't know, but there's no fucking way I'm going back in there," he replied.

Inexplicably, I kept walking -- past the group of students gathered in front of the gymnasium next to our high school and up the steps to the south entrance. My high school is small and contained in a single building --- one hallway on top of another, with a stairway on each side. The hallways have wooden doors that close before you reach the stairwell. I realize now I must have entered the building moments after the shooting took place, because the wooden doors had not yet been closed. I simply opened the doors and looked down the hallway to see several bodies lying in the lobby of my high school.

I turned around and walked out. I wasn't afraid. I didn't panic. I just knew that that building was not a place I needed or wanted to be. I don't remember any physical reaction -- only mind-numbing shock.

The majority of the student body was being directed into the school gymnasium, where pandemonium reigned. I remember being told a friend of mine had died, then minutes later watching her walk through the doors of the gym. Very few of us had cell phones in 1997, so I used my friend's to call my mother. As I stood in the parking lot telling my mother I was safe, another friend ran up and told us the shooter was still on the loose and we should get back in the gym. I remember the panic and dread as we waited for the classes on the second floor to be released from lockdown. Most of my close friends had been upstairs and I remember the relief I felt when I saw them for the first time.

So many had witnessed the shooting that the identity of the shooter himself was never a mystery. His name was Michael Carneal. He was a shy, unassuming freshman. Few knew him personally, but everyone knew his older sister, an outgoing and very involved senior. She and I were in choir together and both worked on the school newspaper staff.

"I didn't even know she had a brother!" were the first words out of my mouth when I found out. Months later, his sister told me he had always been known as her little brother. "Now, I'll always be Michael Carneal's sister," she said.

***

As parents and other adults began arriving, the scene at the school became even more emotional. It was as if we hadn't known to feel sad or scared until we saw the fearful faces of those who were supposed to protect us. When it had been only us filling the gym and trying to figure out what to do, we could keep up a front, but as our mothers and fathers arrived, everything changed. I still remember the sight of cars with doors ajar abandoned for miles up the road as the parents got as close as they could and then got out and ran.

I don't remember when I left or with whom. I spent the evening with friends who didn't attend my high school, telling my story over and over again as the details of the shooting and the names of those injured and killed became known.

Michael Carneal had opened fire on the prayer group that met every morning in the lobby of the school. Three of my classmates were dead and five were injured. Senior Jessica James, sophomore Kayce Steger, and freshman Nicole Hadley were gone. The injuries among the other victims ranged from minor wounds to a classmate who was paralyzed from the chest down.

We learned later that evening that we would attend school the next day. At the time, the decision seemed outrageous. How could they expect us to walk back through those doors so soon? Some of my classmates' parents refused to let them go. However, my mother, a public school librarian, told me that if school was in session, I would be in attendance.

She dropped me off at the front doors of Heath High School the next morning. Directly across the street, the media had set up camp. Satellite trucks and a thick dark line of cameras captured me exiting the car and carrying flowers into the school. I would watch my entrance play out again and again on the nightly news for the next week.

The lobby looked the same as before, except for two small bullet holes in the cement wall that the custodians had already attempted to patch up and paint over. The paint hid nothing as we all went over to peer at the only visual indication that everything had changed. As everyone filtered in, we gathered in a circle. I read a Bible verse, which I don't remember, and added the flowers I brought to the ever-growing pile.

We didn't go to any of our classes that day. There were counselors and ministers there to talk with us. Mostly, we all just wandered around and did whatever felt right. I dedicated myself to forgiveness.

The fact that the shooting had happened during prayer circle seemed significant to me. I had often attended the early morning prayer meeting, and I felt both blessed I had been late that morning and guilty I hadn't been attending the prayer circle more regularly. My simultaneous feelings of guilt and gratitude manifested in a driving desire to forgive Michael Carneal. I went to the library and spent hours making signs with several of my classmates to display in the school windows.

"We forgive you, Michael," they read. There was also the one I can never forget: "We forgive you because God forgave us."

The signs made an impact. Story after story portrayed our community as a place where forgiveness lived. I was interviewed by ABC News with two of my classmates. I held my Bible in my lap and spoke of God's love and how it allowed me to forgive the heinous actions of Michael Carneal.

In my mind, forgiving Michael Carneal meant that I could move on. Even at sixteen, I knew forgiveness was the last step in the healing process. I was not injured. I had not witnessed the shooting. I felt no anger or hatred towards the shooter. Surely this meant I was OK.

So I carried on, and moved along, and grew up. I graduated the next year and went away to college, where I met the man who would become my husband. After graduation, we married and went to law school. I moved back to Paducah and had children of my own. For years, I considered the events of December 1st to be a part of my story, but not a part of who I was.

Small things would affect me, but I never considered them indicative of anything larger. My freshmen year in college, a student died after falling off a cliff during a camping trip. His death felt like a personal assault. I felt as though death and tragedy had followed me far from the grounds of Heath High School. The odd behavior of a trench-coated stranger in a post office would send me hyperventilating, running for the exit. I can still vividly recall the shooting scene in the 2001 film, In the Bedroom, that left me sobbing in the lobby of the theater.

It wasn't until years later that I realized the impact of that day reached far beyond isolated moments of panic. I was sitting with a group of close friends. I'm not sure how the conversation began, but I was telling them that every time my husband and I parted even for a few minutes, to run a short errand, I worried it would be the last time I would see him. My constant fear of losing a loved one in a sudden and tragic way had become a normal part of my life. Every goodbye left me imaging car wrecks or crazed gunmen. If my husband or parents didn't telephone a change in plans or late arrival, I began calling emergency rooms or police stations without hesitation.

I thought everyone felt that way, but as I looked at my friends, it became very clear that the way I felt was not normal. I could see the shock written across each and every one of their faces. I had expected reassurance that they thought the same things from time to time, but instead I received only stunned silence.

***

Over a decade after the shooting at Heath High School, I went to counseling. After only a handful of sessions, my counselor diagnosed me with post-traumatic stress disorder. She told me that the traumatic way I had been introduced to death as a teenager had left me with an unhealthy obsession with it. I began to realize that for years I had lived in fear of December 1st. I had lived in fear of that moment that comes out of nowhere and leaves you broken, shattered, and crying on the floor. I had thought if I could anticipate that moment, if I could prepare for it somehow, it wouldn't be as bad. I realize now the absurdity of that response. The pain of a trauma cannot be lessened or protected against, and I only rob myself of present joys with my futile attempts to do so.

Of course, that realization is hard to hold onto in the aftermath of the tragedy at Sandy Hook. I am now the mother of two small boys -- the oldest of whom will be entering elementary school sooner than I'd like. A level of grief I never imagined at 16 opens up to me when I think of those parents. I knew then that losing a child was terrible thing, but I know now that it is a pain so unimaginable my brain will not allow me to process it. It's as if a security gate slams shut when I try to think about the loss of either of my children. "Do not enter," my brain seems to be saying.

I find myself asking questions that seemed silly when raised by the concerned parents of my classmates 15 years ago. "What are they doing to keep my children safe?" "What security procedures are in place?" As if there were some way to fathom the unfathomable and protect against it.

Mostly, I find myself thinking of the survivors. My classmates and I learned a very difficult lesson in high school. We learned that the world was not a safe place and that truly terrible things can happen when you least expect it. To think of more than 600 students at Sandy Hook Elementary School learning that lesson at nine years old and younger is heartbreaking. I can remember a time when I felt safe, when I didn't constantly anticipate the worst. Perhaps they never will.

They escaped with their lives. But their lives will be forever changed by December 14th. I know this. December 1st taught me.